"It is the ambition of the New Yorker to live upon Fifth Avenue, to take his airings in Central Park, and to sleep with his fathers in Green-Wood.” So wrote Henry J. Raymond, the founder and first editor of The New York Times, in 1866 about the cemetery in southwest Brooklyn that was, like Fifth Avenue and Central Park, one of the most desirable pieces of real estate in the whole of New York City. And with good reason: It “is as lush a landscape as exists anywhere in the built-up boroughs of New York,” wrote architecture critic Paul Greenberger for the Times in 1977. “Green-Wood is one of the most remarkable places in the city.” Not long after it opened in the 1840s, being buried in Green-Wood became a marker of status. But the cemetery’s verdancy and beauty also made it a welcome respite for the living — one so popular with visitors that it inspired the creation of both Central Park and Prospect Park.

Today, Green-Wood Cemetery has nearly 600,000 permanent residents, including some of New York’s most famous (and infamous) politicians, artists, businessmen, and members of high society, as well as thousands upon thousands of ordinary citizens from all walks of life. But it's more than a graveyard; it's essentially a combination of a public park, an arboretum, a history museum, a bird sanctuary, and a sculpture garden. That means that there’s no shortage of things to see and do when you make the trip to Sunset Park.

WHAT’S THERE

A quick note: Maps of the cemetery are provided at each entrance, and they’re highly recommended, as they not only provide the locations of notable gravesites and artworks, but also help keep you oriented amidst Green-Wood's twisty, looping paths and expansive grounds. You can also download a map online and view it on your smart phone, if you prefer a digital version.

Green-Wood also regularly holds events, including guided trolley tours, live musical performances, special after-hours gatherings in the Catacombs, and nature walks. Check out their calendar for more information.

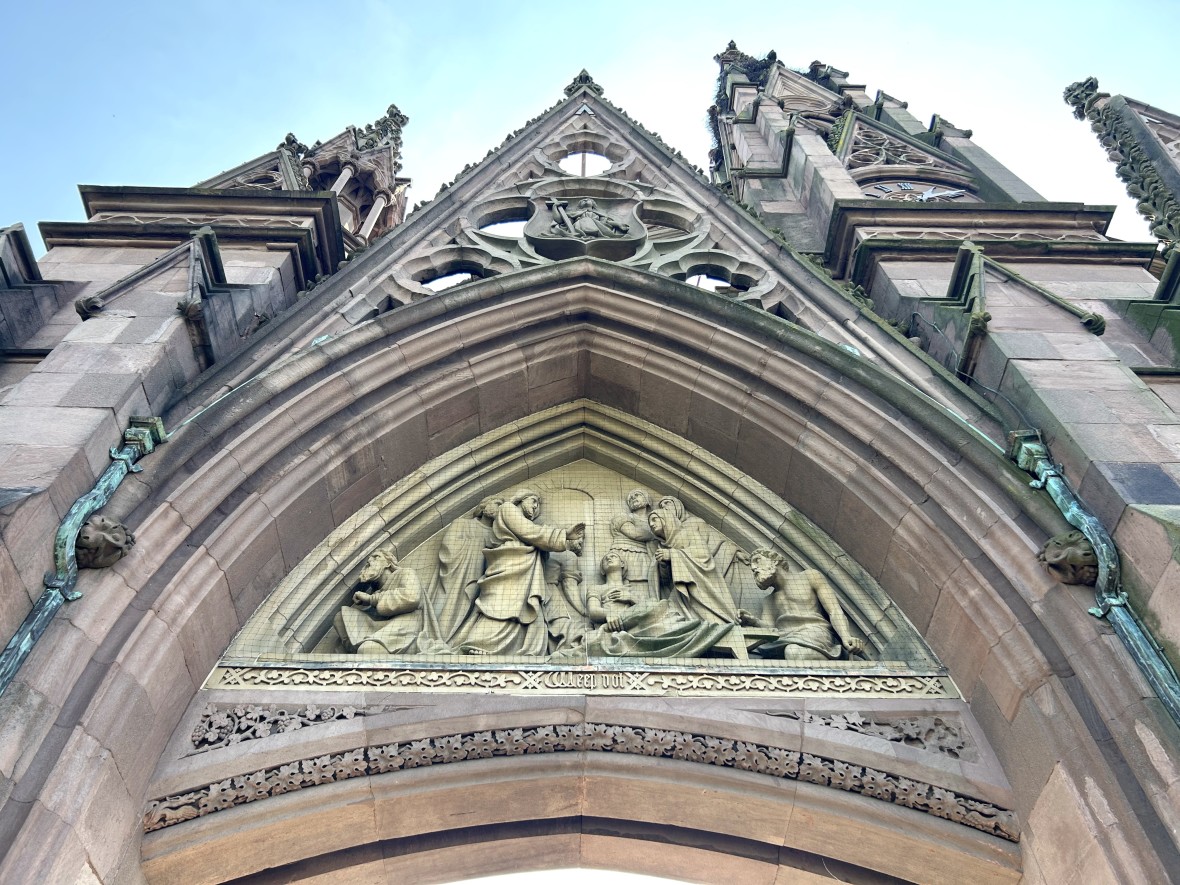

There are four entrances to the cemetery, but the main one is located at 25th Street and 5th Avenue, where you’ll find Green-Wood's iconic gates. Built out of brownstone from New Jersey during the Civil War, they were designed by architect Richard M. Upjohn in the Gothic Revival style and flank a large clock tower, with sculptures of Biblical scenes adorning the facades.

Atop the clock tower, meanwhile, in a sprawling bushy nest, is a colony of monk parakeets. Ordinarily found in South America, these small green parrots are the descendants of a group that escaped a shipping container at John F. Kennedy Airport in the 1960s. The cemetery initially tried to evict them but changed course after finding that the parakeets were better tenants than pigeons, whose droppings erode brownstone. You’ll hear them long before you see them, creating a cacophony of squawks and trills from their lofty perch.

At 478 acres in size, Green-Wood Cemetery is almost as big as Prospect Park and just over half the size of Central Park. And just like Prospect and Central Parks, Green-Wood is a meticulously landscaped greenspace complete with ponds, flowers, grassy meadows and hundreds of trees, some of them almost as old as the cemetery itself. It’s a great place for a long walk, especially since it’s far less crowded than its Park Slope neighbor or its Manhattan imitator. You can go long stretches within Green-Wood without seeing another person, and there are countless areas where you can sit in a grassy area and relax without a (living) soul around.

Birdwatchers, meanwhile, already know that the cemetery is one of the best places in the city to spot our feathered friends, with over 250 species identified and tagged there. The list of birds you can find there is long and diverse: red-tailed hawks, waterfowl of all kinds, dozens of different songbirds, and even such rarities as the scarlet tanager, the yellow-throated warbler, and the rose-breasted grosbeak.

Green-Wood Cemetery is home to some important New York history, too. Before it became a burial ground, it was the site of the Battle of Long Island (also known as the Battle of Brooklyn), the first encounter between British and Continental forces in New York in the Revolutionary War. Fought on August 27, 1776, the battle was an American loss that led to the British capture of New York City, and one of its pivotal moments played out on Battle Hill, which is also the highest natural point in Brooklyn at 220 feet above sea level, near 23rd Street and 7th Avenue. Battle Hill is where you’ll find Minerva and the Altar to Liberty, a sculpture of the Greek goddess Athena (Minerva was her Roman name) erected in 1920 in honor of those who fought and died there. The statue was strategically placed so it would look across New York Harbor and directly at the Statue of Liberty.

Battle Hill is also the site of another war memorial, this one to the New Yorkers who served in the Union Army during the Civil War. Erected in 1869, this 35-foot-tall granite column is adorned with plaques and bas relief sculptures honoring those from the Empire State, as well as four life-size sculptures of Union soldiers. Green-Wood is the final resting place for over 5,000 Civil War veterans, both Union and Confederate, who are largely buried, some in unmarked graves, on the Hill of Graves in the eastern side of the cemetery, close to the entrance at Prospect Park West.

You can also find a slew of Civil War veterans clustered around the nearby memorial to Clarence MacKenzie, a 12-year-old drummer boy who, in 1861, became the first Brooklyn resident to die in the conflict.

Then there are the graves themselves. Among the more notable names that you can find at Green-Wood are:

Jean-Michel Basquiat: The graffiti artist-turned-painter and Brooklyn native was one of the biggest stars of New York’s underground art scene in the 1980s, with his works earning him critical praise and significant financial success. He died of a heroin overdose in 1988 at just 27 years old and is buried in Green-Wood, with a small and simple headstone marking his grave.

Leonard Bernstein: The world-famous conductor and composer and former music director of the New York Philharmonic, who died in 1990, is buried at Green-Wood next to his wife, Felicia Montealegre, who died in 1978. Their plot lies near Battle Hill; Bernstein was interred with a conductor’s baton and a copy of the score of Gustav Mahler’s Fifth Symphony.

Alice Cary and Phoebe Cary: The Cary sisters were two of the most celebrated poets of their time and, after moving from their home in Ohio to New York City in 1850, hosted Sunday evening receptions attended by the major figures of art and literature in the city. Both died in 1871 and were buried together in Green-Wood; the pallbearers at Alice's funeral included P.T. Barnum and Horace Greeley.

Henry Chadwick: Dubbed “the Father of Baseball,” Chadwick was an early proponent of the sport and an important figure in its growth into a professional enterprise in the late 19th century. Fittingly, his grave features brass sculptures of bats, a glove and a catcher’s mask, and is bounded by four bases connected by a path. (You’ll also find a few actual baseballs left by well-wishers.)

DeWitt Clinton: A two-time governor of New York State, Clinton left a long legacy as a politician, including his backing of the Erie Canal, which transformed New York into an economic powerhouse. Clinton died in office in 1828 and was originally buried in Albany, but in 1844, his remains were disinterred and moved to Green-Wood Cemetery, followed by a memorial monument in 1853. His burial there helped make it a desirable graveyard and popularize it as a tourist attraction.

Charles Ebbets: The former owner of the Dodgers and namesake of their Flatbush stadium died in 1925 and was buried in Green-Wood along with members of his family.

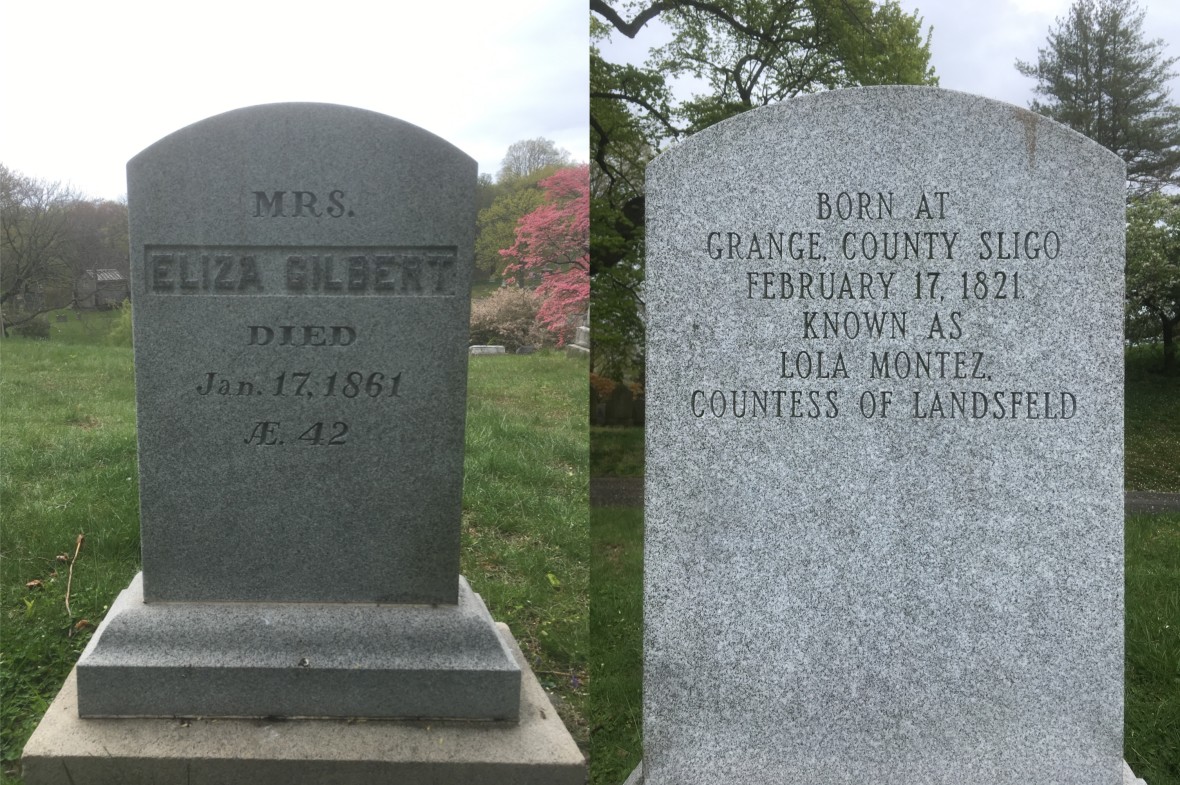

Lola Montez: Born Eliza Gilbert, Montez was an Irish actress and dancer known for her beauty and vivacious personality. In 1846, she became the mistress of King Ludwig I of Bavaria and acted as a power behind the throne until his abdication in 1848. She was reportedly the inspiration behind the character of Irene Adler in Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories. Her grave has both her birth and stage names on it, as well as the title given to her in Bavaria: Countess of Landsfeld.

Samuel Morse: The inventor of the telegraph, Morse was also an accomplished painter and an arts professor at New York University. Born in Massachusetts, he died in New York City in 1872.

Henry Steinway: The German-born founder of the Steinway & Sons piano company lies in the cemetery’s largest private mausoleum, one that holds not only his remains but also those of several family members, including his wife, his five sons, and his 10 grandchildren. It cost almost $50,000 to build (roughly $1 million in today’s money).

Susan McKinney Steward: The first Black woman to earn a medical degree in New York State, Steward was born in Crown Heights in 1847 and attended New York Medical College, graduating as the class valedictorian in 1869. As a doctor, she worked mostly in prenatal care and childcare, and she was also an active and passionate social reform advocate.

William “Boss” Tweed: The longtime head of Tammany Hall, which controlled city politics in the 1860s and 1870s, Tweed was a former Congressman who used the patronage system to install his allies in important positions across New York, deliver votes for Democratic candidates, and enrich himself in the process. Convicted on corruption charges in 1873, he died in prison in 1878, but despite Green-Wood's rules against burying anyone who had died in jail, his family managed to secure him a grave there.

Green-Wood Cemetery was also the place where everyday New Yorkers were buried and remembered. Names known only to friends and family can be found on gravestones and mausoleums throughout the grounds, often inscribed with Bible quotes and simple descriptors: Mother, Father, Son, Daughter, Husband, Wife. While the great majority of them were neither rich nor famous, in their passing, their families built them monuments befitting lords and millionaires to honor them in death. Perhaps the best way to enjoy Green-Wood Cemetery is to stroll among the obelisks and columns and ornate tombstones and quietly contemplate the passage of time.

HISTORY

New York City in the early 1800s had a huge problem: It stank.

The city's growth from a small colonial settlement to the center of American commerce brought about a population boom; the number of residents tripled between 1800 and 1830. But space was limited, and that was especially the case in New York’s few graveyards. By 1820, Trinity Church on Wall Street had over 100,000 people interred in its two-and-half-acre burial ground, with bodies frequently stacked one on top of the other. And all those decomposing corpses produced a perpetual foul odor that was impossible to escape. Things reached a breaking point in 1822, with an outbreak of yellow fever that summer fueling fears that the miasma produced by New York’s overflow of bodies was leading to disease epidemics. That year, a ban was passed on burials south of Canal Street, and the search began for a new home for the deceased — ideally one that was far from the increasing urban sprawl.

In 1838, a group of civic leaders led by Henry Evelyn Pierrepont, an early city planner, purchased 178 acres of farmland in Brooklyn in what is now Sunset Park with the goal of turning it into a bucolic rural cemetery. Pierrepont was inspired both by his trips abroad to historic cemeteries in Europe, and by the recent creation of similar burial grounds in the United States like Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Laurel Hill in Philadelphia. Two years later, Green-Wood Cemetery held its first interment, and by the 1860s, it had become a draw for both the dead and the living, who would picnic on the grounds and take carriage rides along its paths. At that time, it was the second-most popular tourist attraction in all of New York State, trailing only Niagara Falls in terms of annual visitors at 500,000 each year.

WHEN TO GO AND WHAT TO KNOW

Green-Wood Cemetery is open from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. every day of the year, and admission is free. Though you’re welcome to walk the grounds at your leisure, don’t mistake the cemetery for an outdoor gym: Jogging and other physical activities are prohibited. Bicycles and scooters are not allowed within the gates; nor are pets. You can bring a snack or a drink with you into the cemetery, but there’s no picnicking allowed on the grounds. Shutterbugs and birdwatching aficionados are free to bring their cameras and take photos. Public restrooms are available and located at the various entrances.

HOW TO GET THERE

The main entrance to Green-Wood Cemetery at 25th Street and 5th Avenue is a short walk from the 25 St R train station at 4th Avenue. You can also take the F or G trains to the cemetery; get off at 15 St-Prospect Park and walk to the northern entrance on Prospect Park West and 20th Street or go to the Church Av station and walk to the eastern entrance on Fort Hamilton Parkway at Micieli Place. Or you can ride the D or N trains to the 36 St station at 4th Avenue and enter the cemetery on the southwest corner of the grounds through a pathway one block north of the station. Learn more here.