Welcome back to our new series, Have You Been?, where we will visit stops off the subway, bus, Long Island Rail Road, and Metro-North lines, and offer our top 3 picks (and a little bit more) for each destination to help you plan your next train trip. Our next stop is Washington Heights and Inwood.

Visiting Washington Heights and Inwood can feel like taking a trip back in time. Manhattan’s two northernmost neighborhoods are dotted with reminders and remainders of the city’s past dating back to its pre-colonial days, including the last vestiges of the old-growth forest that once covered the island from tip to tip. Over the years, these neighborhoods — comprising roughly three square miles of land from 155th Street up to the end of Manhattan — have gone from farmland to a suburban getaway to one of the city’s most densely packed areas, populated by Dutch and German farmers and wealthy 19th century New Yorkers looking for open green spaces and waves of Irish and Jewish and Dominican immigrants. But even amid all the change, both Washington Heights and Inwood retain a unique, idiosyncratic character — simultaneously a crush of cultures and, in many ways, an oasis of calm, solitude and nature that stands in stark contrast to Manhattan’s relentless urbanity.

There’s no shortage of things to do or see in Washington Heights and Inwood, but where should you start, and what should you make sure to check out? Here’s our guide to two of the city’s most diverse neighborhoods, where you can both pound the pavement and disappear amidst the trees on the same day.

A LITTLE BIT OF HISTORY

Washington Heights and Inwood were inhabited well before European colonizers came to New York’s shores. The Wecquaesgeek and Lenape peoples lived, hunted and farmed in the area, establishing long trails between Lower Manhattan and the Hudson Valley — trails that over time became the basis for Broadway and St. Nicholas Avenue. When the Dutch arrived, they gradually pushed out the natives and parceled out northern Manhattan as farmland and for private use, a practice continued by the British when they purchased the land in the early 18th century. During the Revolutionary War, several notable battles were fought in the area, including the Battle of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776, a decisive British win that helped them secure control of the city, which they held until the war’s end.

Following independence, Washington Heights and Inwood became popular among the city’s wealthy residents; removed from the noise and crowding of Lower Manhattan, the open fields and verdant forests offered quiet refuge and plenty of land to build large, palatial estates.

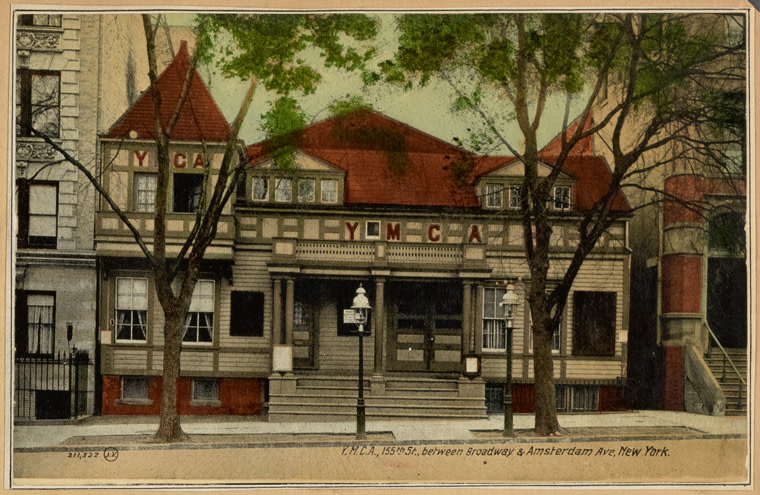

By the beginning of the 20th century, apartments began to replace the mansions as the city’s growing population required more room. Between 1900 and 1920, the population of Manhattan north of 155th Street boomed from 8,000 to 110,000, spurred by the expanding public transit system making its way up the island. Many of the newcomers to the neighborhood were European Protestants, followed by Eastern-European Jews and Irish immigrants. In the post-World War II era, Black New Yorkers expanded into the area from Harlem, and as white residents left the city for the suburbs in the 1950s and 60s, Latinos increasingly moved in. Today, Washington Heights and Inwood have the largest population of Dominicans outside of the Dominican Republic; of the roughly 200,000 people who live in both neighborhoods, about two-thirds are Hispanic or Latino.

Here are our top three picks for what to see in both neighborhoods.

1. THE MET CLOISTERS

Atop a high hill in Fort Tryon Park is a gateway to the Middle Ages. Opened in 1938 and run by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cloisters is a series of enclosed gardens within a building reminiscent of a Medieval French abbey or monastery, featuring art from the 12th-15th centuries acquired in Europe by American art dealer and sculptor George Gray Barnard in the early 20th century. What separates the Cloisters from a typical art museum, though, is its immersive quality. Throughout, you’ll find stained glass, colonnades, tomb effigies, chapels, apses, sculptures, tapestries, murals, mosaics, and the cloisters themselves, each reconstructed from abandoned or demolished abbeys or monasteries. Those cloisters each frame individual gardens and function as light, airy spaces amid the heavy walls and dark rooms of the building itself.

There are literally thousands of artworks within the Cloisters, most famously The Hunt of the Unicorn, an exquisite 15th-century Flemish tapestry. But what makes the Cloisters a must-see is the atmosphere of it. Unlike its big brother on the Upper East Side, it isn’t bursting to the brim with tourists; at times, you’ll find yourself virtually alone amid the art. It’s less a museum and more a quiet place to commune with the art. That’s especially true of the gardens in the cloisters; even in early spring with a chill in the air, they make for a wonderful place to sit and relax as birds chirp and bumblebees float from flower to flower collecting pollen. The same is true of the area around the Cloisters — speaking of which…

2. THE PARKS

Forget Central Park and Prospect Park; if you want to disappear into nature, come to Washington Heights and Inwood. Each boasts some of the best park land in all of New York City, from the giant expanses of Inwood Hill and Fort Tryon to the smaller yet still serene spaces dotting the streets.

Atop the island is Inwood Hill Park, which stretches for 200 acres north of Dyckman Street and represents perhaps the only place in Manhattan unchanged by the hand of man. The natives called it Shorakapok, a name that translates variously to “the edge of the river” or “the sitting place” in the Munsee language used by the Wecquaesgeek, who used to live in what is now the park. Although Dutch and British colonizers (and later New Yorkers) cleared acres of land for development, much of the old forest remained untouched.

Officially designated a park in 1916, Inwood Hill is a beautiful place to lose yourself. Three trails, each ranging between one and two miles, wind their way through the trees and provide a hearty yet doable climb for amateur hikers. Bird-lovers will find plenty to enjoy, too; Inwood Hill is a popular bird-watching site, where you can find (or at least hear) blue jays, cardinals, wrens, and more, including, if you’re lucky, bald eagles. And thanks to Inwood Hill’s location on one of the island’s highest points, you can enjoy sweeping views of the Hudson River and New Jersey, as well as the Henry Hudson Bridge and the Spuyten Duyvil Creek at its northern end.

Step out of Inwood Hill Park at its southern end and you’ll practically stumble right into the area’s other major park: Fort Tryon. Named after the last British governor of colonial New York, the land that makes up Fort Tryon Park — 67 acres — sits between 192nd Street and Dyckman Street, with Broadway to the east and the Hudson River to the west. The land was acquired by John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1917 and given to the city in 1931 for use as a park; before that, it was a home for natives in pre-colonial times, and then a space for estates in the 19th century. Today, it’s where you can find the Cloisters, several gardens, and panoramic views of the Hudson River, the Palisades, and the George Washington Bridge.

There are two other parks worth noting in the area. Right next to Inwood Hill Park is tiny Isham Park, the former site of a mansion built by a 19th-century leather merchant named William Isham. There, he constructed a summer estate and farm; upon his death in 1909, much of the land was given to the city, which turned it into a park. The house Isham built was long ago demolished, but the grounds are a pleasant mix of manicured lawns and stately trees, and like Inwood Hill Park, it makes for a secluded and quiet area to enjoy some space and peace.

Further downtown at 185th Street, you’ll find Bennett Park, site of the highest point in Manhattan (265 feet above sea level) and the aforementioned Battle of Fort Washington. The land was bought by New York Herald publisher James Bennett Sr. in 1871 and passed down to his son James Jr. when he died just a year later; the city bought the land in 1928 after the latter’s passing. Today, the park is largely a playground, though its historical importance makes it worth a stop.

3. THE LITTLE RED LIGHTHOUSE

Built in 1931, the George Washington Bridge is a marvel of engineering, and the busiest motor vehicle bridge in the entire world; over 100 million cars pass over the Hudson every year using the span. But underneath the bridge sits a tiny structure no less notable or famous: Jeffrey’s Hook Light, also known as the Little Red Lighthouse. The subject of a beloved children’s book, the Little Red Lighthouse is, to this day, the only lighthouse in the entirety of Manhattan.

In 1921, the US Coast Guard bought and dismantled a lighthouse in Sandy Hook, New Jersey and rebuilt it on Jeffrey’s Hook, then a treacherous obstacle for passing ships. But the lighthouse had stood for just 10 years before the George Washington Bridge and its powerful electric lights opened, rendering it obsolete; in 1948, the Coast Guard officially decommissioned it. That would have been the end of Jeffrey’s Hook Light, but when the Coast Guard announced plans to dismantle and auction it, they were met by public outcry thanks to the lighthouse’s starring role in Hildegarde Swift’s 1942 book The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge, in which the bridge seeks the help of the lighthouse to warn boats of danger and reassures it that it still has a role to play. Children from across the country wrote letters and sent money to save the lighthouse, and in 1951, the Coast Guard reversed course, selling the lighthouse to the city, which added it to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

Although you cannot go into the lighthouse except when tours are arranged by the Parks Department, you can still visit it in Fort Washington Park. Dwarfed by the bridge, it nonetheless remains as a link to the city’s past and a cultural marker, and one well worth seeing.

MORE EXPLORING

If you’re looking for a hands-on history lesson, head to the Morris-Jumel Mansion in Washington Heights. The oldest still-standing house in Manhattan, it was built in 1765 by a British colonel, was used by General George Washington as a military headquarters in 1776, and occupied by a French wine merchant after the turn of the century. Purchased by the city in 1903, it exists today as a museum, with rooms preserved in their 18th- and 19th-century heyday. Access to the mansion requires a paid ticket, but you can walk through the small park around it for free. If you do visit, make sure to check out Sylvan Terrace, a small one-block cobblestone street adjacent to the mansion featuring some of the last existing wooden houses in New York City.

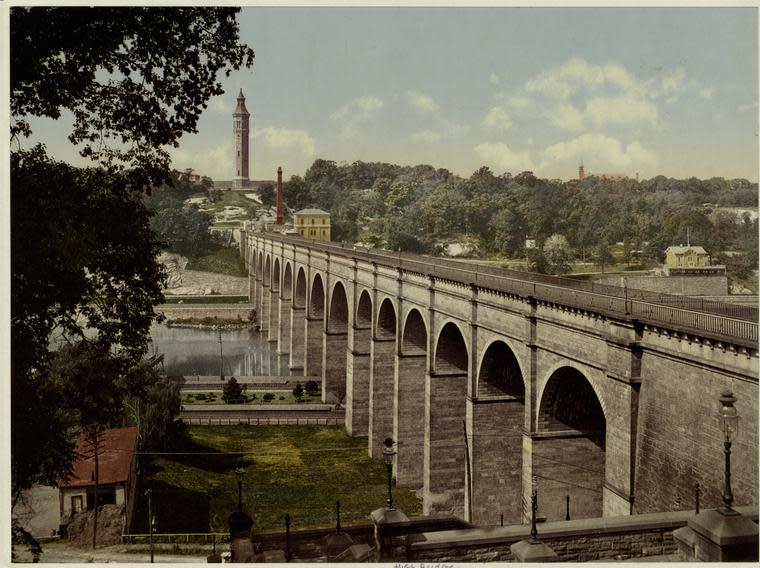

Near the Morris-Jumel Mansion, you can find Highbridge Park and the High Bridge, a once prominent promenade and the oldest standing bridge in New York. Connecting Washington Heights with Highbridge in the Bronx, it was once part of the city’s former aqueduct system that brought water all the way down from the Croton Reservoir in the 19th century.

Baseball history fans already know that Washington Heights was the location of the Polo Grounds, the home of the then-New York Giants from 1891 to 1957. When the team decamped for San Francisco ahead of the 1958 season, the stadium played host to the Mets and Jets before being demolished in 1964 and replaced with public housing projects. The only thing that remains of the Polo Grounds is the John T. Brush Stairway, named after the team’s owner; it connects Edgecombe Avenue to the Harlem River Driveway at Coogan’s Bluff, which overlooked the stadium, at 158th Street.

The Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum is the final resting place for a number of famous New Yorkers, such as author Ralph Ellison, actor Jerry Orbach, naturalist John James Audubon, former New York governor and senator John Adams Dix, the industrialist John Jacob Astor IV, and four mayors, including Civil War-era Confederate sympathizer Fernando Wood and Ed Koch. It's also the only active cemetery in Manhattan. Spend some time winding between the graves and the worn-away tombstones of New Yorkers long gone.

Similar to the Morris-Jumel Mansion, the Dyckman Farmhouse is the last of its kind — in this case, the oldest farmhouse still standing in Manhattan. The structure dates back to around 1785 and was the property of the Dyckman family — the same family that gave its name to Dyckman Street, which runs across Inwood from the Hudson to the Harlem River. (It is, for all intents and purposes, West 200th Street.) The Dyckman family once owned 250 acres of farmland in northern Manhattan, and the farmhouse was their home for nearly 100 years. Today, it's a museum dedicated to depicting life in colonial New York.

The United Palace is a masterpiece of melded architectural styles, blending design elements from Rococo, Persian, Art Deco, Byzantine, and Moorish construction and art (and much more). Originally opened as a movie theater in 1930, it was purchased in 1969 by a televangelist named Rev. Franklin J. Eikerenkoetter III, aka Reverend Ike, who turned the building into the home of his United Church Science of Living Institute. Today, it's a city landmark used for concerts, the occasional film screening, and other live performances.

WHERE TO EAT

Walk down Broadway in Washington Heights and Inwood and you’ll probably find at least one Dominican restaurant on every block. There’s no shortage of places to get excellent pernil, mofongo, roasted chicken, and other Dominican specialties, but consider this a vote for Malecon (4141 Broadway). If you can tear yourself away from watching rotisserie chickens spinning in the window, you’ll be treated to a terrific meal off an expansive menu. Don’t skip out on the rice and beans or the maduros.

For a slightly different culinary experience, head to Flor de Mayo (4160 Broadway) for a fusion of Peruvian and Asian food, aka Chino-Latino. Lomo saltado and Peruvian roast chicken are the standouts, as is the pepper steak.

For a meal on the go, check out Floridita (4162 Broadway), which specializes in Cuban and Dominican food. Grab their Cubano and enjoy its savory cuts of pork and ham with mustard on perfectly garlicky bread as you walk through the neighborhood.

Need a cup of coffee or a quick breakfast? Salento (2112 Amsterdam Ave) is a Colombian cafe where you can snack on specialties like pandebono or buñuelo plus fruit pastries and fuller breakfast options like huevos pericos (scrambled eggs with onions and tomato) or calentado (a rice-and-beans stir fry topped with a fried egg).

GETTING THERE

Washington Heights and Inwood can be reached at a variety of subway stops on the 1, A and C lines. On the 1 train, you can get off at any stop from 157 St to 215 St; on the A, you can get off at any stop between 168 St and Inwood-207 St; on the C, you can get off at 155 St, 163 St, and at the end of the line at 168 St. (Fun fact: the 190 St A train station and the 191 St 1 train station are the deepest stations in the subway system.)

Subway

No matter where you are in Washington Heights or Inwood, there's always a subway station close by

Where have you been lately? Let us know about your favorite train stop destination by tagging @MTAaway on your social media posts.